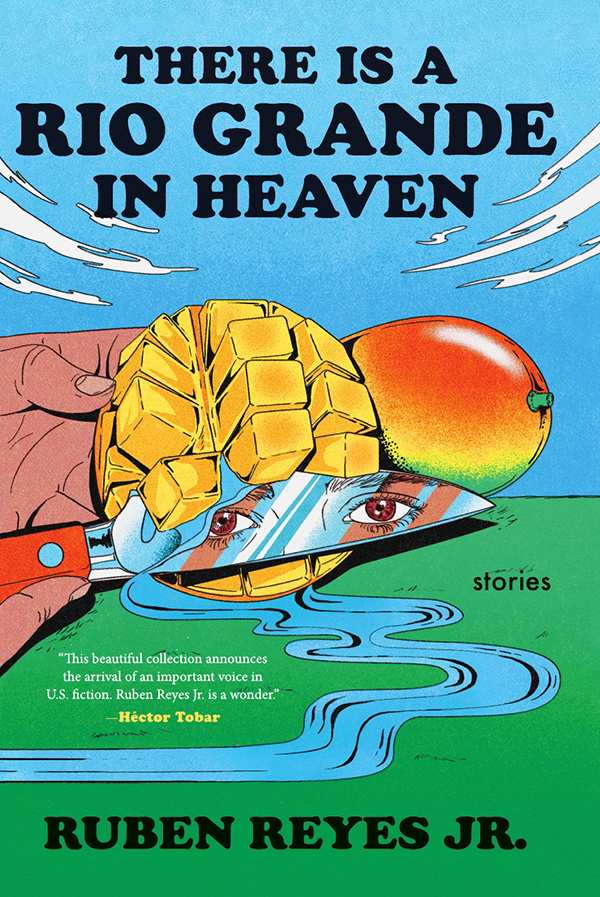

Much lauded by critics (Kirkus Reviews, Back Shelf Books, Book Browse) and Central American diaspora organizers in multiple cities and the like, There is a Rio Grande in Heaven won Reyes, Jr. a lot of success and adoration in a small corner of Latino lit. I struggled to see what the fanfare was about. Here is my take by take:

Alternate History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World - I was unimpressed with this story as it plays out a romantic fantasy of indigenous resistance in a really fanciful way. It doesn’t actually consider the material historical circumstances and what it would have taken for the Pipiles to fight off Pedro Alvarado. Instead, it imagines Alvarado as a stand-in for what was an entire imperial enterprise that could not be ended by simply killing off one man. In this sense, it gives Alvarado FAR too much credit. This story also didn’t acknowledge the indigenous collaboration with the conquest of El Salvador by Tlaxcaltecans, Zapotecs, and the like. To me, it reads like the decolonial fantasy of someone who has barely read history, who has yet to truly grapple with the rich material at hand.

He Eats His Own - This story seems successful in that it would be a great conversation piece to talk about privilege of the diaspora versus those in the homeland. In this story, a rich gay diasporic Salvi named Neto pays his loved ones in the homeland to send fresh mangos from a specific tree to him regularly. The fixation is pathological in its intensity. As far as a premise goes, the symbolic choice of the mango is apt and the scene is set for some interesting tension.

The weirdest parts of this story to me, however, are its seemingly unintentional absurdities. The one that frustrates me the most is the description of the main character cutting the mangos in six perfect pieces. This is dramatically absurd. No one who cuts mangos regularly could write this. Anyone who cuts mangos knows that they are cut in 5 pieces: two short, two wide, and the seed. As an oblong fruit, there is no geometrically possible way to cut it in six pieces that could be described as “perfect”, especially considering that fruit is natural and therefore comes in imperfect shapes. This bore greater explanation.

Absurdities like these riddle the relationships in this story. For example, the family dynamics don’t make any sense. How does Neto maintain such close ties with his homeland family exclusive of the rest of his family? How would he be able to hide Tomas being in the States without the rest of his family knowing? How would he be able to hide the death of the mami from them? Why would they be afraid of leaving Tomas alone? Yes, he’s a child but he made it across the desert with the coyote. The suggestion that a starving child would have made it across the desert without eating the mango was really bizarre and required the suspension of critical thinking in a way that troubled me. There’s many moments where it’s just like, this isn’t how rational people would behave.

That said, it’s interesting. Not moving by any means, but interesting in the conversations it seeks to spark about tensions between diaspora and homeland relations.

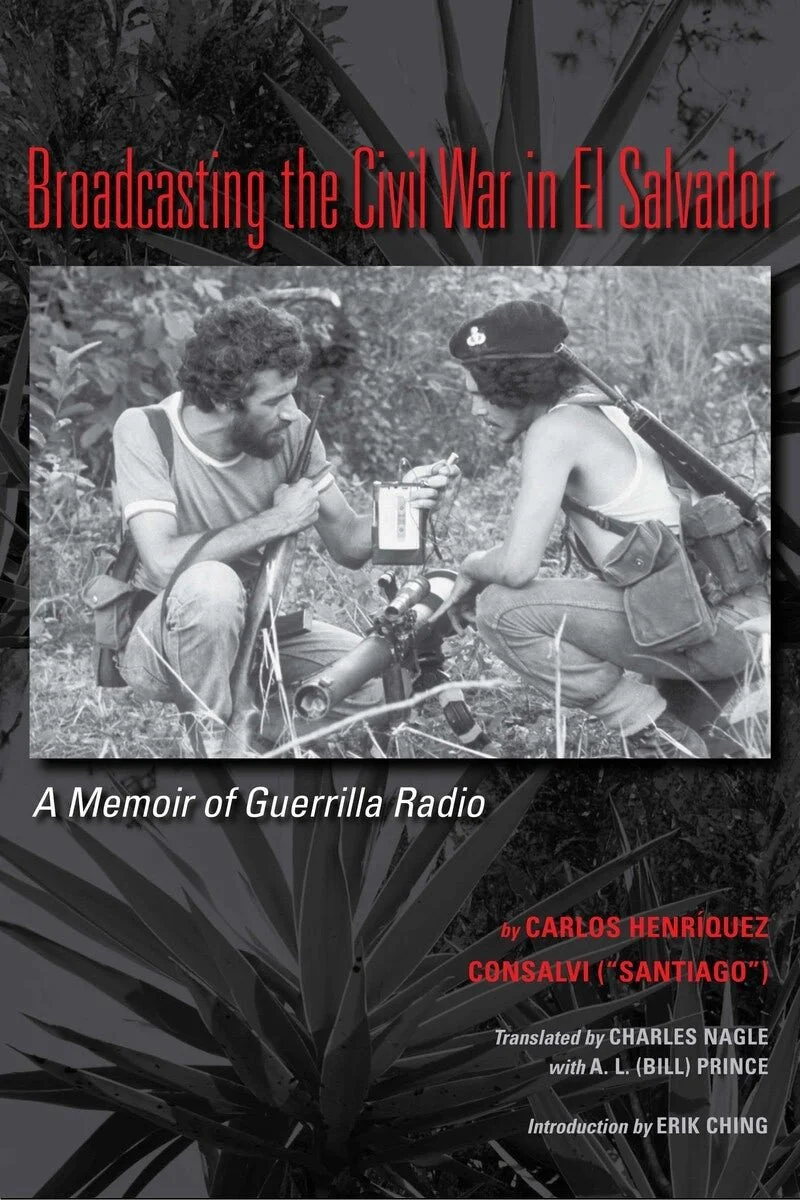

Try Again - In this story, a gay man chooses to resurrect his father through an AI bot. His father was a homophobic poet who survived the civil war. It was a sad, probing story, and one of the better stories in the collection.

An Alternate History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World II - Clean, slick story about General Martinez rearranging peasant bones from mass graves into a dinosaur. This is one of the stronger stories in the collection.

The Myth of the Self-Made Man - This is perhaps the best story. In this story, companies invent cyborg nannies/slaves by mining migrants’ bodies and erasing their memories. While the setup was appropriately gross and kinda hard to get into, by the time it gets to the migrant’s stories, the story gets really compelling. This story probably would’ve been better as a novel, as it doesn’t feel developed all the way. The main character doesn’t seem to go through a transformation of any sort, which is pretty standard narrative craft. While there’s an interesting critique of academic scholarship’s failure to do more than document sometimes, I was ultimately left feeling like very little was done with such a juicy concept.

Quiero Perrear! and other Catastrophes - This story is insultingly bad. A dude wakes up as a reggaeton star with a dark gay secret in a story that asks for the reader to repeatedly suspend their critical thinking skills to follow the plot. There are multiple unexplained instances of memory loss and identity transformation/disappearance. This amount of critical thinking I had to suspend to attempt to enjoy this story depressed me. Like none of Reyes’, Jr. editors or press gave a shit about his craft if they let this story get through. The story ends with a big “it was all a dream.”

By this story, I was stunned by the repeated appearance of a neurotic bisexual or gay male character in this short story collection. At least two deeply struggle with social acceptance. It’s a weird note to hit over and over again, and the reggaeton story feels like the epitome of this poorly explored cliche of the bisexual man fighting his demons.

Alternate History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World (Selena Story) - This story is simply unforgivable coming from a Salvadoran author. In it, Selena never gets famous, but instead, a Salvadoran singer and rising star later covers Como La Flor and she’s the beloved one instead of Selena. This story reads like a confession that Reyes’ Jr believes Salvadoran-American identity is just a pale desperate echo of Mexican-American identity, something the worst of our Mexican peers are suspicious of already. That combined with the title There is a Rio Grande in Heaven makes it feel like Reyes, Jr. is begging to be misread as a Mexican.

My Abuela, the Puppet - This story could inspire great discussion about the way children of the diaspora use their parents’ stories, which is a really worthy, juicy, and fat premise. That said, I wish this story modeled how to engage with our family’s stories, rather than simply providing a critique of how some folks do it. Because we must engage with our family’s stories, and if we do not, they will be written by our enemies. White people are dominating the market and media with their stories. We need more robust, fierce, loving conversations about it.

The Salvadoran Slice of Mars - There seems to be a trend of writers placing a story on Mars and thinking that’s enough to make the story interesting. In this way, writers are at times giving the tech elite’s delusions and, more often than not, outright swindling air time. In a story like Try Again, their failure to actually create functional technology is at least acknowledged. But in stories like the Salvadoran Slice of Mars, the idea that they can actually manage to get us to Mars is taken seriously, and that in and of itself feels like a kind of failure. Of course, I’m sure there are good Mars stories out there. I just have not encountered one. This felt like an unserious dive into climate fiction.

An Alternate History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World - In this story there is a pandemic that only affects Salvadorans. This story simply made me sad, not in a particularly insightful or beautiful way. Just sad. The fact the pandemic doesn’t kill them is strange, I guess, but otherwise, it’s at least logical enough besides that.

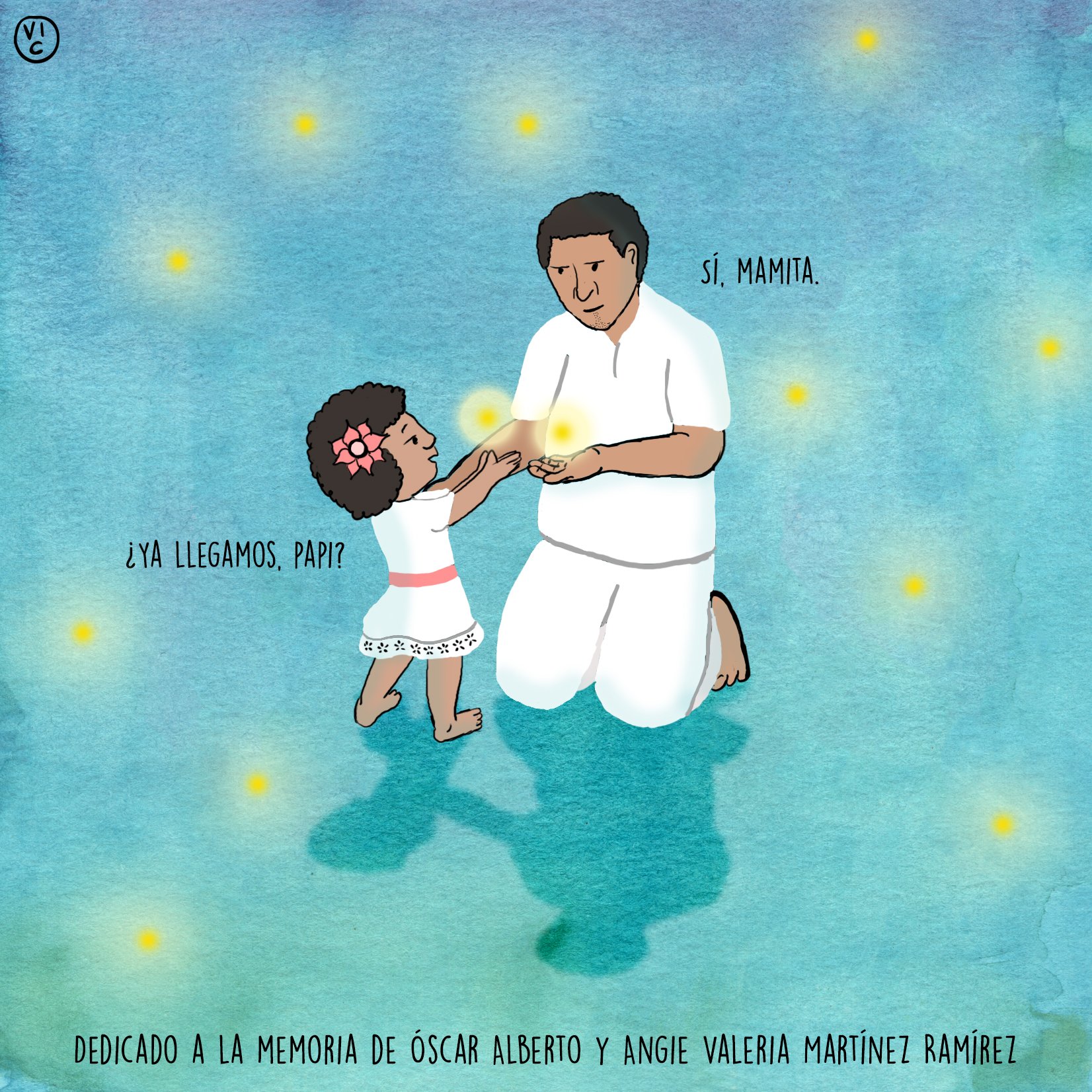

Variations on Your Migrant Life - This is a choose your own adventure story. The game-ification of this deeply commonplace and tragic story felt pretty odd to me. Weirdly enough, by giving the reader agency, it feels like Reyes, Jr. takes away agency from the life of the character. Formally, I was a little disappointed at how deterministic this makes the plot. Maybe that’s the point. Either way, the story is told almost in complete summary, which knocks some wind out of its sails. The story was universalized and not particularized, which frustrated me. That said, I was moved by the part where Reyes’ Jr describes the questions that undo your family and put it back together. There was also this banger of a phrase about “the line between desire and action is like a river between two nations.”